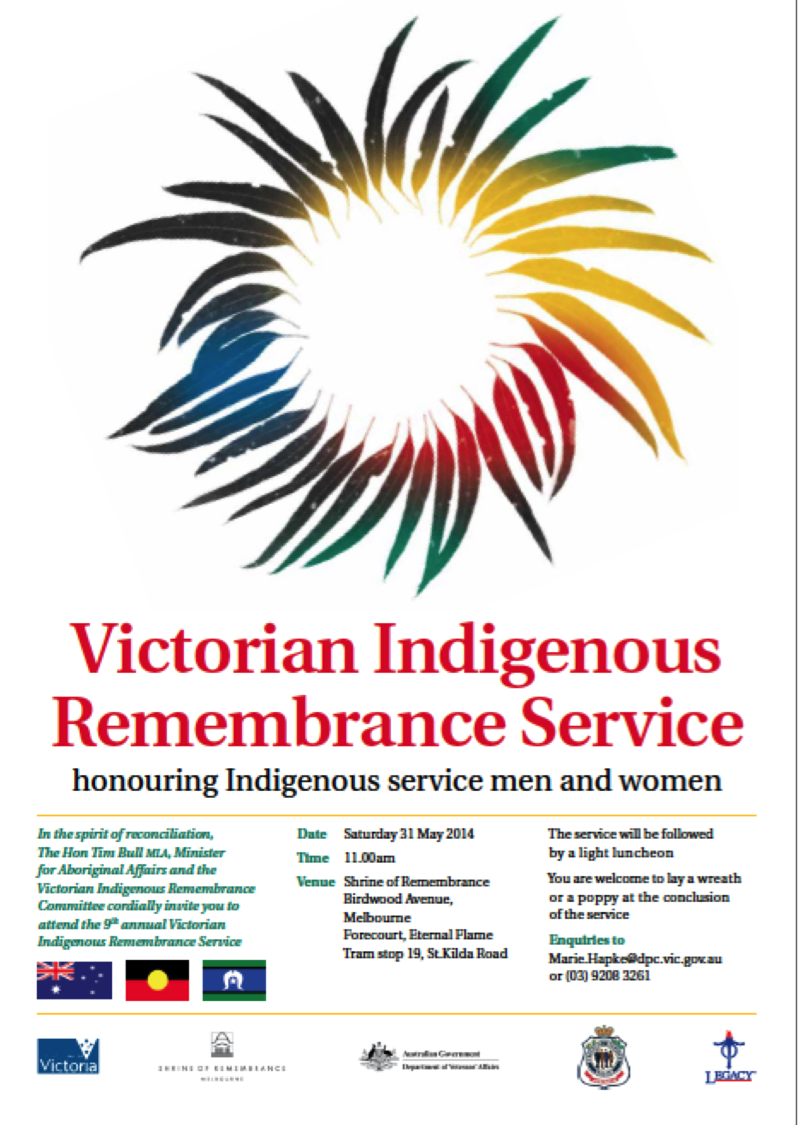

Come to the Shrine of Remembrance in Melbourne Saturday May 31st 2014 and learn more about the Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples’ service in defence of Australia.

Category Archives: WWII

British war graves to be restored in northern Poland

Prisoners of War: They are soldiers, who must have encountered the enemy in close quarters and gone through an individual, and perhaps group, process of deciding to fight to the death, lay down their arms in defeat, exhaustion, injury, abandonment or at the lost of all hope.

The encounter, the surrender or capture, for a soldier is, I suspect one of the most gut wrenching feelings a person could be faced with. Perhaps there was a feeling of relief – I’m safe at last: I will rest out my days in a camp and just wait until this awful War to end all wars is over. Some camps horrific, some civilized. But to die in captivity is something that is unimaginable.

At times there was kindness in death, but the captors, priests, nuns or a wreath provided by a surrounding occupied town, but largely dying as a prisoner of war in captivity in an unconscionable end to the of a teacher, plumber, a baker, father or a son.

It is important to remember them, and restoration of their final place headstones and monuments is important.

First World War Centenary, 1914-1918

The graves of 39 First World War British soldiers who died at the German army’s Heilsberg prisoner of war camp are to be restored.

The graves, at Lidzbark Warminski in northern Poland, were marked with a Cross of Sacrifice and Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) headstones in the years immediately following the end of the conflict. But, during the 1960s, the cemetery deteriorated and the men’s names were added to the memorial at Malbork Commonwealth War Cemetery.

Restoration

Experts from the CWGC are now restoring the Lidzbark Warminski site, erecting new headstones that have been manufactured in the CWGC’s offices at Arras in France.

A number of families of the men have come forward and will be able to attend a rededication ceremony planned for May, at which the CWGC will also install a new Visitor Information Panel.

Among those commemorated at Lidzbark Warminski is 19-year-old private Frank Bower…

View original post 25 more words

All Quiet on the Western Front

I too have been reading All Quiet on the Western Front after only glancing through it in the 1980’s school book assignment. Thirty years later, I’m ready to really read it and contemplate what all soldiers and animals (mainly horses) when through 100 years ago. #ANZAC

I’ve been reading the book All Quiet on the Western Front by Erich Maria Remarque and it’s one of those books that when you look at the cover you’re like “ehh looks slow” but once you start reading it, it really grabs you and you want to keep reading. It’s about a soldier and his fellow soldiers on the battle field of World War 1 and how things were from their point of view. I had always heard of WW1 and WW2 and I always had an idea that is was a struggle for soldiers who fought, but my idea of their struggles was just death and starvation. Little did I know that they had lice, trench foot, and barely showered. It’s much worse than I thought it to be. Books like these sort of “humble” you in a way. For a while you put your life into perspective and…

View original post 34 more words

The last World War Two soldier

I was in a rush one day before Remembrance Day and quickly ducked into Quinton’s IGA in Warrandyte for some groceries. As I entered, I passed an elderly gentleman seated with this tray full of poppies fund-raising for the Returned Services League (RSL) of Australia. He had a baseball cap on and, like most men of a more respectable era, dress pants and an a jacket despite the warm weather. On his lapel were several badges and of course, a blood-red poppy. I back tracked, ignoring my urge to rush in and out of the shop as quick as I could, with my conscience telling me I needed to buy a poppy.

As I passed over my donation to support veterans, I asked the old Digger when did he serve. He answered “World War Two, I’m the last one.” I paused for a moment, thinking about of his understated remarks, ladened with a magnitude of meaning that I could not ever really hope to comprehend. Firstly, this proud but frail man sitting in the grocery store had served in a battle so great it is titled a “World War.” How could anyone who had never served on a battlefield hope to understand what that meant?

As I passed over my donation to support veterans, I asked the old Digger when did he serve. He answered “World War Two, I’m the last one.” I paused for a moment, thinking about of his understated remarks, ladened with a magnitude of meaning that I could not ever really hope to comprehend. Firstly, this proud but frail man sitting in the grocery store had served in a battle so great it is titled a “World War.” How could anyone who had never served on a battlefield hope to understand what that meant?

Secondly, I was caught off guard by simple but powerful words “I’m the last one.” I tried doing arithmetic about WWII, did he mean the last standing Digger in Australia or this local area or his battalion? I had to ask, but it did not matter if he was the last one in the country or the last one in the local area, anyone who says they are the “last one” of a group of friends, soldiers or a generation carries a heavy burden.

He was the last WWII Digger of the Warrandyte RSL Club.

The Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) and the term “Diggers” became famous during the drawn out battles of WWI. The name Diggers has stuck to Aussie soldiers for over ninety years – not only known for their courage under fire, but their ability to dig in under the arduous circumstances.

RSL Club’s once graced nearly every town in Australia and are familiar as the proverbial kangaroo to Australians of all ages. Once flooded with returned soldiers from both World Wars and later Korea and Vietnam, the Clubs have slowly emptied, some closing their doors, ‘consolidating’, as Diggers from the Great War, then the following wars, slowly thinned in their ranks with the passing of time.

The rush of modern-day life then caught up with me, I had to move on: get the shopping done, get the kids and get moving. But that thirty-second conversation stayed with me, played on my mind…. “I’m the last one” and soon there would be none. I wondered if someone had captured his story, recorded his thoughts, this Last Digger of Warrandyte. The last of his generation. The last of his mates.

Many weeks passed and I started a documentary photography course at Melbourne’s RMIT University under the direction of esteemed photographer Michael Coyne. We had to come up with subject ideas for our portfolio of photos and this Last Digger came to mind. My final project concept ended up being “Roundabout to Roundabout”, documenting life between Warrandyte’s two roundabouts, starting at the CFA Fire Station and ending at the Roundabout Cafe several kilometres away.

Many weeks passed and I started a documentary photography course at Melbourne’s RMIT University under the direction of esteemed photographer Michael Coyne. We had to come up with subject ideas for our portfolio of photos and this Last Digger came to mind. My final project concept ended up being “Roundabout to Roundabout”, documenting life between Warrandyte’s two roundabouts, starting at the CFA Fire Station and ending at the Roundabout Cafe several kilometres away.

By this stage Remembrance Day had passed and there was no sign of the Last Digger at the local IGA. I would have to do my project without the poppy seller in my portfolio of life between the roundabouts. As I spent too many hours stalking people and businesses along Warrandyte Road, I got used to the rhythm of the old township, got to know the shop keepers by day and even several by night as the project developed.

And then on the last day of my portfolio shooting in Warrandyte, I saw in the distance a man in a baseball cap with a bit of a slow shuffle, making his way between the roundabouts. Despite the hot day, he was well dressed with a jacket and slacks and had his tray of RSL knickknacks in hand, still fundraising for current veterans and their families well passed Remembrance Day.

In one of my next blogs I will tell the remarkable story of the Last Digger of Warrandyte. In the meantime, I encourage anyone who knows a WWII soldier to ask them about their service… before it is too late.