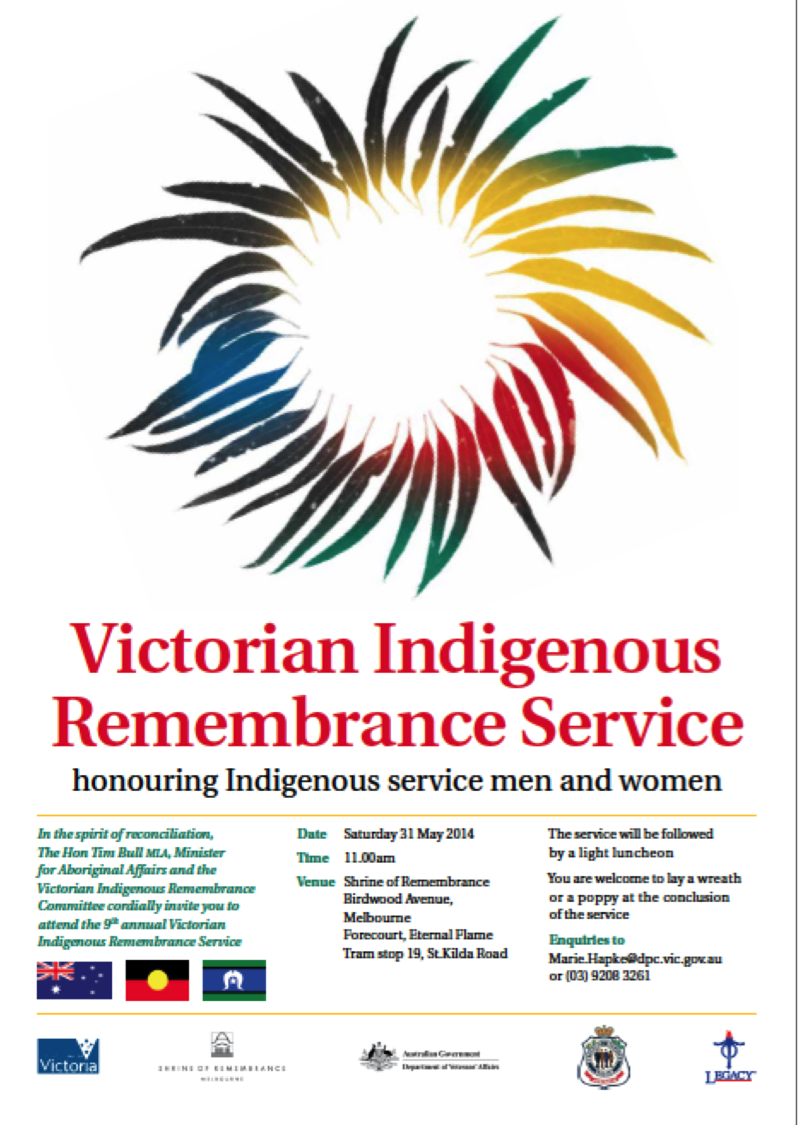

Come to the Shrine of Remembrance in Melbourne Saturday May 31st 2014 and learn more about the Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples’ service in defence of Australia.

Category Archives: WWI

Artists and authors, starting out can be hard

Being an author, blogger, researcher, performer, artist… the list goes on and on – it can be hard. Here are some pointers from my recent blog post on going it alone, whether you are a historical researcher or small gallery or historical society, check it out :

Being an author, blogger, researcher, performer, artist… the list goes on and on – it can be hard. Here are some pointers from my recent blog post on going it alone, whether you are a historical researcher or small gallery or historical society, check it out :

“Many entrepreneurs start out as a one-man (or woman) show. While this can be challenging, exhausting and incredibly rewarding, ultimate success may not be determined by your business idea, but by how organised you are.

Experienced freelancers and small businesses that are single person operations need to be ultra-organised. Whether you are flying solo for the first time or well established, technology can improve your efficiency and performance. Here are some pointers based on my own experience running a one-man show.”

See full article here: The Pulse

Four opticians that became ANZACs in WW1 – one survived

An outdoor portrait of the 9th Training Battalion at Perham Downs, Wiltshire. Victorian optician Gordon Heathcote from Kew is seated on the far left, sporting his new Corporal stripes he earned in England.

Cpl Gordon Roy Heathcote, 24th Company Australian Machine Gun Corps.

Cpl Gordon Roy Heathcote was an optician of Kew in Victoria. Single, twenty-three years old and living with his parents comfortably in Melbourne’s inner eastern suburbs, he enlisted in August and set sail from Melbourne on 20 October 1916. Seated on the left above, the machine gun is not just a prop for the photo – this optician had landed as a non-commissioned officer in an Australian Army Machine Gun Corps. Single, living with his parents comfortably in Melbourne’s suburbs. he enlisted in August and left Melbourne on 20 October 1916. In was promoted to Corporal while in England and completed his physical and bayonet training courses there before landing in France in September 1917. He was killed in action just short of a year after leaving his in Melbourne, dying on 16 October 1917 in Belgium. The soldier standing behind Gordon with his arm reached onto his shoulder is, Frederick Benedict (Ted) Alsop, who died the next day on the 17 October 1917.

Photo courtesy of the Australian War Memorial P08299.007

2nd Lt George Stanley McIlroy, 24th Battalion, of South Melbourne.

2nd Lt George Stanley McIlroy,

24th Battalion, of South Melbourne.

An optician prior to enlistment, he was awarded the Military Cross, “for conspicuous ability and gallantry as a Company Commander throughout the operations in France from 26 March 1916. He looks well after his men and has set them a fine example of soldierly endurance under heavy shell fire at Pozieres. His Company has done excellent work throughout, and this is due in great part to the powers of leadership developed by Captain McIlroy”. Due to illness, he returned to Australia on 17 March 1917.

Photo courtesy of the Australian War Memorial P05891.001

Lt Arthur Douglas Hogan

21st Battalion from Lewisham, NSW.

Arthur was a 29 year old jeweller/optician prior to his enlistment in 1915. After arriving in Egypt, he was repatriated back to Australia suffering from typhoid. Following his recovery, he then wounded but returned to the front and was killed in action at Passchendaele in 1917. Lt Hogan is commemorated on the Menin Gate Memorial, Ypres, Belgium with others who have no known grave.

Photo courtesy of the Australian War Memorial H0575

Captain John Needham, 2nd Pioneer Battalion, VIC, Australian Imperial Forces.

This is a story of a First World War (WWI) optician: mentioned in Despatches by General Sir Douglas Haig, Commander-in-Chief of the British Armies in France for “distinguished and gallant services, and devotion to duty” in the 2nd Pioneer Battalion, Australian Imperial Forces (AIF).

Born in 1882, John V Needham enlisted at age 19 in the Victorian (Mounted Rifles) Contingent he served in South Africa and returned in 1902. As a young Boer War Veteran, Needham then joined the Victorian Scottish Regiment and later married, having a son and training to become an optician. He was a practising optometrist/refractionist at Richmond, an inner suburb of Melbourne, before he enlisted as an “optician” in the AIF in late 1914.

Seated in the front row, first left, is Captain John Valentine Needham, a Boer War Veteran, father and optometrists, who left his business in 1914 to answer the call of the AIF. One of the few “opticians” that appear in the #WW1 ANZAC records, his became a front leaders, suffered shell shock, was wounded and returned home a five years later. This is his story. Photo courtesy of AWM p00988.031

The term optician in 1914 may have equated to what we would think of as a modern-day “optometrist” including a store front and dispensary. Doing eye testing, cutting and fitting of lenses and offering a section of frames including custom-made styles, all was probably completed and dispensed to the customer at the Richmond building.

The professional organisation of Australian optometrists was is its infancy at the time and a search of the Australian War Memorial & National Archive of Australia records for opticians, optometrist or optometry reveal very few WWI enlistment records, except Captain Needham, enlisting with such an occupation.

Later wounded and of failing health, the Optician was now a front line officer in France, and worried about his business affairs at home: “He sleeps badly and worries that his business in going to ruin in Melbourne… He has insomnia and tremors of the hands…stress and strain from active service conditions.”

He saw service in Gallipoli and France and was promoted to captain in 1916. Wounded and ill, he was recommended for the Military Cross for his gallantry at Pozieres, but Mentioned in Despatches, his health deteriorated. A report recommended he be returned to Australia in 1916 as unsuitable for active duty, but other medical evaluations determined he was fit for duty. Sadly, it took another three years before he arrived home in Melbourne in 1919.

He saw service in Gallipoli and France and was promoted to captain in 1916. Wounded and ill, he was recommended for the Military Cross for his gallantry at Pozieres, but Mentioned in Despatches, his health deteriorated. A report recommended he be returned to Australia in 1916 as unsuitable for active duty, but other medical evaluations determined he was fit for duty. Sadly, it took another three years before he arrived home in Melbourne in 1919.

A broken man, he never recovered and was hospitalised because of the trauma of war. He died in Melbourne in the early 1920s. His death was considered to have been directly caused by his service.

Seated in the front row, first on the left, is Captain John Needham, the “Optician” from Melbourne, in an outdoor portrait of officers of the 2nd Pioneer Battalion, Australian Imperial Forces, c. 1916. His WWI awards & recommendations included:

- 1914-15 Star : Second Lieutenant J V Needham, 24 Battalion, AIF

- British War Medal 1914-20 : Captain J V Needham, 2 Pioneer Battalion, AIF;

- Victory Medal : Captain J V Needham, 2 Pioneer Battalion, AIF;

- Mention in Dispatches

- Recommended: Military Cross

In addition, Captain Needham received the Queen’s South Africa Medal for the Boer War, all of which are now held in the national collection of the Australian War Memorial.

Soldiers who paid the ultimate sacrifice received the honour of a Memorial Scroll from the King and saucer-sized bronze plaque recognising their service to the Empire. The later was often called a death penny. His widow had wrote on many occasions to receive his entitlements, for his young son, and eventually she received a Memorial Scroll from the King but added to one letter:

Soldiers who paid the ultimate sacrifice received the honour of a Memorial Scroll from the King and saucer-sized bronze plaque recognising their service to the Empire. The later was often called a death penny. His widow had wrote on many occasions to receive his entitlements, for his young son, and eventually she received a Memorial Scroll from the King but added to one letter:

“P.S. I would also like one of the Memorial Plaques – as next of kin – if this is not asking too much. A. G. N.”

Information sourced from Australian War Memorial and National Archives of Australia internet sites 25 April 2014. (C) Andrew McIntosh CPA

Last Post: Remembering the First World War

Throughout the world researchers, writers, bloggers and family members are becoming familiar with “Field Post” cards. For many years official histories and formal records dictated much of the content of #WW1 history. With the passing of the Great War generation, often the men first and then their partners, more and more First World War post cards are becoming available.

Be this via opening your grandparents musty box of letters or finding a card from the Great War at a market, early postcards are growing in popularity as a low-cost method for collectors, students and writers to get up close and personal with #WW1. Unlike war sites being reclaimed by nature, post cards are had written – a piece of history actually handled by the soldier, the nurse, the veterinarian on the front line.

Often the Field Post cards will have a last portrait or show the ruins of Europe, but you often get the sense of fore boding: you can sense the “she’ll be right mate” attitude of Aussie Diggers as they face an uncertain and often deadly future. Now with the advent of online websites like eBay, cards posted from Field Post Offices are cheap and readily accessible to all.

The unexpected twist is when the enemy post cards appear and you see that not only the fresh face youth of the British Empire which was marched to muddy hell, but also the proud young German men, writing home to their mothers, sisters and girls-friends. Field Post Offices provided an amazing service in so many ways.

While technology brings us close to accessing WWI messages, the world faces losing much of the modern-day message from the battle field: email and social media is quick, easy and instantaneous – yet go back through your emails and you may find they are slowly disappearing. 9-11 for example: the emotion, heart-break and agony of that day would have been once on paper or post card. Look back through your emails and see if you have any from September 11th, 2011.

I know my email service provided does not retain anything that old now. Fortunately, a little old-fashioned I know, I printed out the key emails of the time. I am glad I did, because a great bulk of that electronic ‘field post’ for this century, email, does not have a life span of the documents handled by the Great Field Post Offices of the War to End All Wars.

British war graves to be restored in northern Poland

Prisoners of War: They are soldiers, who must have encountered the enemy in close quarters and gone through an individual, and perhaps group, process of deciding to fight to the death, lay down their arms in defeat, exhaustion, injury, abandonment or at the lost of all hope.

The encounter, the surrender or capture, for a soldier is, I suspect one of the most gut wrenching feelings a person could be faced with. Perhaps there was a feeling of relief – I’m safe at last: I will rest out my days in a camp and just wait until this awful War to end all wars is over. Some camps horrific, some civilized. But to die in captivity is something that is unimaginable.

At times there was kindness in death, but the captors, priests, nuns or a wreath provided by a surrounding occupied town, but largely dying as a prisoner of war in captivity in an unconscionable end to the of a teacher, plumber, a baker, father or a son.

It is important to remember them, and restoration of their final place headstones and monuments is important.

First World War Centenary, 1914-1918

The graves of 39 First World War British soldiers who died at the German army’s Heilsberg prisoner of war camp are to be restored.

The graves, at Lidzbark Warminski in northern Poland, were marked with a Cross of Sacrifice and Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) headstones in the years immediately following the end of the conflict. But, during the 1960s, the cemetery deteriorated and the men’s names were added to the memorial at Malbork Commonwealth War Cemetery.

Restoration

Experts from the CWGC are now restoring the Lidzbark Warminski site, erecting new headstones that have been manufactured in the CWGC’s offices at Arras in France.

A number of families of the men have come forward and will be able to attend a rededication ceremony planned for May, at which the CWGC will also install a new Visitor Information Panel.

Among those commemorated at Lidzbark Warminski is 19-year-old private Frank Bower…

View original post 25 more words

Australian Indigenous Response to World War One

Book Review: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Volunteers for the AIF: The Indigenous Response to World War One (Second Edition 2012)

Author: Philippa Scarlett

Private Harry Avery with an unidentified Aboriginal soldier (previously thought to be Douglas Grant) and an unknown British soldier, c 1918, courtesy of Rebecca Lamb.

I first came across Philippa Scarlett’s name as part of my research into World War One Australian Aboriginal soldier Douglas Grant. Philippa was a guest on an ABC Radio program with two other researchers, Garth O’Connell and David Huggonson. Garth and David had led the way some years earlier by documenting the neglected area of Australia’s Indigenous war service record.

The radio program had the well known portrait of a WWI Aboriginal soldier, standing next to Private Harry Avery and an unknown British soldier, as a prominent image on it’s website for the interview. This photo, said to be of Aboriginal…

View original post 412 more words

All Quiet on the Western Front

I too have been reading All Quiet on the Western Front after only glancing through it in the 1980’s school book assignment. Thirty years later, I’m ready to really read it and contemplate what all soldiers and animals (mainly horses) when through 100 years ago. #ANZAC

I’ve been reading the book All Quiet on the Western Front by Erich Maria Remarque and it’s one of those books that when you look at the cover you’re like “ehh looks slow” but once you start reading it, it really grabs you and you want to keep reading. It’s about a soldier and his fellow soldiers on the battle field of World War 1 and how things were from their point of view. I had always heard of WW1 and WW2 and I always had an idea that is was a struggle for soldiers who fought, but my idea of their struggles was just death and starvation. Little did I know that they had lice, trench foot, and barely showered. It’s much worse than I thought it to be. Books like these sort of “humble” you in a way. For a while you put your life into perspective and…

View original post 34 more words